15 Oct 2018

Wounds in companion animals: benefits of good management (2)

Ross Allan considers approaches to treating these injuries – including debridement and bandaging – in part two of his article.

In the first of this two-part article (VT48.24), the author discussed the physiology and classification of wound closure; part two will explore the various strategies and techniques to support the healing process itself.

With many bandaging and wound care products claiming to improve wound healing, an understanding of how and when to use these products will ensure they are used effectively.

Immediate wound care

The descriptions that follow assume the patient has undergone a full clinical assessment and has been stabilised as necessary – paying particular attention to effective analgesia in the trauma patient.

In all contaminated wounds, the bacterial contamination can be significant, and a vital first step is to reduce and minimise this infection risk. Basic steps – such as covering wounds with sterile dressings to help reduce contamination, washing hands and wearing gloves during examination – are important to reduce iatrogenic wound infection risk.

The time since injury is important. The “golden period” is generally considered to be the time from initial injury until the bacterial contamination has increased to reach 10⁵ per gram of tissue. Debate exists over exactly what the “golden period” is – some suggesting it may be as short as three hours, and others saying around six hours. More than six hours does mean a wound will be contaminated and it is likely bacteria will have colonised the wound, therefore it should be considered infected. Managing wounds at this stage will often require profound sedation or general anaesthesia, and the suitability of this will depend on concurrent trauma and patient status.

Hair removal is an important first step in wound management. Wide clipping, using an aseptic technique, will reduce the risk of further contamination, make dressing application easier and often uncover wounds that were not already visible. Iatrogenic damage to the tissue during clipping is to be avoided and filling wounds with a sterile lubricant is a useful technique to minimise damage at this time.

Lavage is a vital step to reduce bacterial contamination of wounds. Care has to be taken, however, to use enough pressure to dislodge debris and contamination, while not causing local tissue damage or driving material deeper into wounds. The consensus is still unclear on an ideal pressure for decontamination for each patient, but, in general, a pressure of 8psi to 12psi – created using an 18-gauge needle attached to a 20ml syringe, often via a three-way tap – can work well. The lavage is frequently performed at an angle so as to lift debris from the wound.

A safe and effective means of decontamination is 0.9% saline, and it is usually a good choice for wound lavage. Tap water has been shown to cause fibroblast injury in dogs; therefore, it is not recommended (Devriendt and de Rooster, 2017).

How much lavage? Ultimately, the purpose is to maximise the reduction of contamination, and this will depend on the individual wound, but will often be 500ml to 1,000ml, and unlikely to be less than 150ml.

Following clipping and lavage, it is essential to assess for damage to neurovascular and anatomical structures. It is important to perform this assessment at an early stage to ensure concurrent injuries are not missed – a factor that can play a part in their successful management.

It is also important to aseptically prepare the periwound as this will prevent migration of bacteria from this area into the site of the wound. Sterile exploration of puncture wounds is also to be advised, using a blunt-ended object such as a Spruell needle. Penetration injuries can extend beyond the area expected, as this can significantly alter the management plan.

Local antibiotics

While topical wound powders were once commonly found on the shelves of many practices, and used for acute wounds, their use is now not advised. Instead, culture and sensitivity testing of contaminated wounds following wound lavage, and then starting empirical systemic therapy (such as with amoxicillin-clavulanic acid), is often employed while awaiting the results of the culture results.

Wound dressings

- Tape stirrups. Use of surgical tape with or without assistance from a moisture vapour permeable spray dressing.

- Primary (contact) layer. The choice of this will depend on wound type and stage.

- Secondary (conforming) layer. This is to support the dressing, protect the wound and keep the patient comfortable. Synthetic conforming bandages wick moisture away from the wound – reducing the risk of problems. The conforming layer may also utilise knitted bandages overlying the synthetic conforming bandage.

- Outer layers. The use of bandages is an effective means of providing support and protection. Non-adhesive bandages that are sweat and water resistant easily mould to the shape required. Care should be taken when applying these bandages to avoid excessive pressure, especially at sites where there is a risk of pressure necrosis.

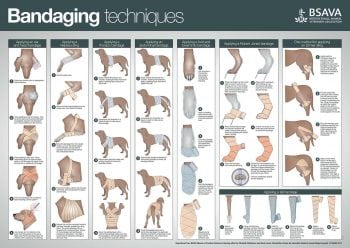

During the past 10 years, the variety of dressing material for wound management has increased largely and greatly improved our options. Before choosing an advanced material, all of us in practice will recognise the ability to apply a safe, secure, but not too tight, dressing is a key skill; therefore, the author suggests all practices should consider acquiring a resource such as the BSAVA’s poster on bandaging techniques (Figure 1).

This skill – first in theory and then in practice – comes with experience. Making owners aware dressings are not without a risk of causing damage, and using phrases such as “it is better they fall off than be too tight“, and advising of the signs of discomfort are conversations that, in the author’s opinion, are essential when applying any dressing – no matter how small or seemingly innocuous. All dressings generally have three key elements (Panel 1), but it is the contact layer that has the largest choice.

Debridement

Removal of necrotic, foreign and contaminated tissue from the wound is an essential first stage for managing contaminated wounds and various dressings exist to support this process.

Surgical debridement

In some wounds, definitive surgical excision of the damaged tissue prior to primary surgical repair can be considered, and may indeed simplify matters, but this will greatly depend on the anatomical area concerned, wound size and position, as well as the surgeon’s confidence in being able to accurately assess the true extent of the damaged tissue.

Staged/layered debridement

In some wounds, such as degloving injuries in the first few days, assessing the areas that require to be surgically excised is difficult: areas that look damaged may survive, and others that appear healthy will become necrotic. This challenge can mean staged surgical debridement, over a number of days, in conjunction with non-surgical debridement, which can allow the opportunity to assess the wound regularly with the aim of minimising non-essential debridement. This approach may be especially appropriate for extensive degloving-type injuries, where wounds are in the vicinity of key structures and excision may carry particular risks.

Non-surgical debridement

Wet-to-dry bandages

Wet-to-dry bandages were once the recommended means of removing necrotic tissue and microbial contamination from wounds. Sterile saline-moistened swabs are applied to the wound under more dry swabs. As the fluid is wicked the contact swabs dry, adhering to the necrotic tissue, then detach that tissue when removed from the wound.

Discussion is increasing on whether this is a preferred means of debridement, as wet-to-dry dressings are non-selective, with inevitable damage caused to healthy granulation tissue at the same time as removing necrotic tissue. Therefore they should only be used during the inflammatory phase. They are also painful to remove, so patients must be heavily sedated and the need for regular dressing changes can be a concern.

That said, in heavily contaminated wounds it is the author’s opinion that aggressive surgical debridement, often in combination with short-term wet-to-dry dressings, can allow swift removal of necrotic tissue and provide a basis for progressing to the next stage of wound healing.

Selective debridement – topical enzymatic agents

Usually referring to the use of proteolytic enzymes that can “detach” unhealthy, non-viable tissue from viable tissue, interest is increasing in these selective debridement techniques. They do have recognised advantages: minimal bleeding or pain and avoiding trauma, but do take longer than surgical or wet-to-dry, non-selective debridement techniques, and this may make them unsuitable for many veterinary patients.

Honey dressings

Various theories exist on the benefits of including honey in dressings. These include their hyperosmolar benefits, a low concentration of hydrogen peroxide that is believed to have antimicrobial qualities and the presence of antimicrobial phytochemicals. Anti-inflammatory properties and an impact on lymphocytic/monocytic cellular stimulation are believed to occur.

While issues exist transferring human studies to our veterinary patients, a Cochrane review concluded that, while honey dressings did appear to help partial thickness burns and infected postoperative wounds to heal more rapidly than conventional dressings, beyond these comparisons the evidence was of low quality (Jull et al, 2015).

Moist wound healing

The aim of all initial wound management is to get to the stage when moist wound healing can be employed. Moist wound healing maintains an optimal local environment for wound healing – cells and growth factors stay in the wound, and are not removed with excessive dressing changes. It also promotes atraumatic selective debridement as supporting a moist wound allows the body’s natural proteolytic enzymes to dissolve necrotic tissue, therefore allowing macrophages to mop up the tissue debris (Thompson, 2017). Hydrophilic dressings perform this well and can be used in conjunction with hydrogels if required to supplement the exudate naturally present from the wound.

Increasingly this “one-size-fits-all” view is being revised and specific hydrophilic dressings, which can more optimally suit the individual wound – specifically, its anatomical location and amount of exudate – are being used. These dressings, such as those containing alginate, seek to further optimise the environment for rapid granulation and epithelialisation.

Silver dressings

Silver-impregnated dressings have been available in human health care for some time – the belief being they have antibacterial effects, perhaps by altering the growth factors present within the wound. The use of silver sulfadiazine (1% ointment) has been replaced with silver-impregnated hydrophilic dressings.

While some evidence exists of its possible benefits, unfortunately very little has been published about the use of silver dressings in veterinary medicine. Likewise, in human medicine little strong evidence exists to support the use of silver dressings.

A Cochrane review stated “there is not enough evidence to recommend the use of silver-containing dressings or topical agents for treating infected or contaminated chronic wounds” (Vermeulen et al, 2007), while another Cochrane review warned “insufficient evidence [exists] in promoting wound healing or preventing infection” (Storm-Versloot et al, 2010).

Advanced techniques

Negative pressure

Interest has increased in the use of negative pressure wound therapy, with evidence of reducing excessive interstitial fluid, thereby improving vascular supply to the wound, while also physically stimulating a more rapid fibroblast mitotic rate and improve granulation tissue production (Demaria et al, 2011; Nolff et al, 2015).

Access and availability to this technique is increasing, with scope to hire the required equipment for the process. This may increase access to what is a developing and exciting area in veterinary wound management, often used in conjunction with hydrophilic dressings and/or skin graft techniques (Stanley, 2017).

Conclusion

Effective management of the open wound prior to delayed primary closure or secondary closure is, in the author’s opinion, one of the true “arts” of the profession, based on a thorough understanding of the wound type, stage and progression. Managing these cases, which often visit the practice, is challenging yet rewarding and a skill that requires dedication, good communication, and a clear understanding of wound healing and the hurdles encountered along the way.

Despite what, at times, can seem daunting, challenging wounds – no matter how tricky – they can be some of the most rewarding patients to treat.

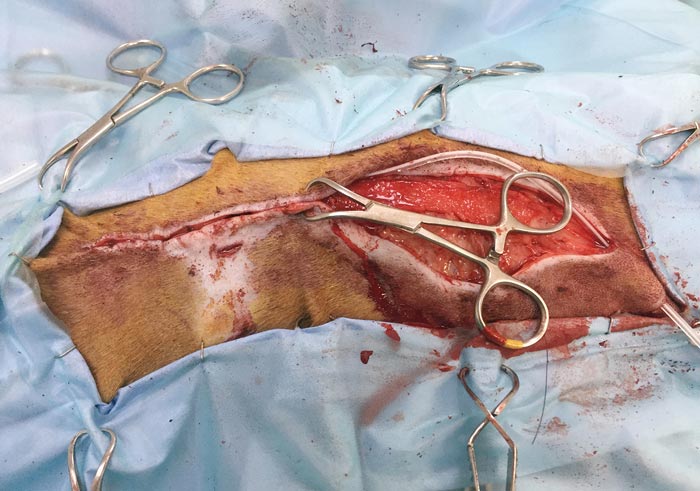

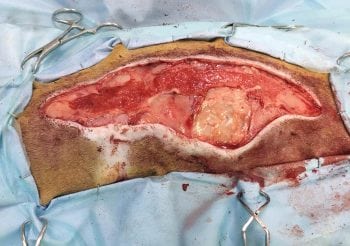

Case study 2. A burn injury in a six-year-old whippet

This dog presented for management of a thermal burn. It was treated first by excising the necrotic tissue, then wet-to-dry dressings to remove that tissue, followed by applying hydrophilic dressings to promote granulation over the damaged area.

The full extent of damage caused by chemical or thermal burns (such as that from heat pads) can take a few days to become fully apparent. The severity or grade of the burn takes into account its depth, as well as the body surface area affected (Pavletic, 2018), and appropriate systemic and local treatment is important in the immediate period following injury.

Burns are a risk we need to be conscious of when treating our patients. Two notable examples of this are inadequately connected monopolar diathermy units and the use of heat pads. In the latter, it is essential the whole clinical team understands the danger of heat pad burns, and what steps should be taken to reduce their risk. In particular, care should be taken with thin-haired and skinned animals, such as whippets and Italian greyhounds. The Veterinary Defence Society reported it handled 17 civil claims in 2016 and 23 in 2017 (personal communication) – indicating a need exists to maintain awareness of the risk of these injuries.

Burns may be managed surgically or non-surgically – dependent on the grade and anatomical location of the injury, with removal of necrotic tissue being an important step.

Latest news

Small animal

Long-term use of NSAIDs in canine osteoarthritis: what does the evidence tell us?

Sponsored

1 Aug 2025