2 Feb 2015

Use of flukicides in dairy cattle

Liver fluke disease is caused by internal trematode parasite Fasciola hepatica. In dairy cattle it causes economic losses due to weight loss, diarrhoea, decreased milk yield and occasional death (Pritchard et al, 2005).

In addition it has the capacity to modulate the host’s immune response, altering susceptibility to, and diagnosis of, other pathogens including bovine tuberculosis.

The most recently published survey indicated 76 per cent of English and 84 per cent of Welsh dairy herds had been exposed to liver fluke (McCann et al, 2010). A more recent unpublished study of 606 high-yielding dairy herds in late 2012 found 79.7 per cent to have positive bulk tank ELISA results (Williams et al, 2014).

Due to increasing resistance to triclabendazole and the introduction of restrictions on the use of flukicides in dairy cattle in July 2013, knowing which product to use when is an important part of liver fluke control.

Life cycle and disease

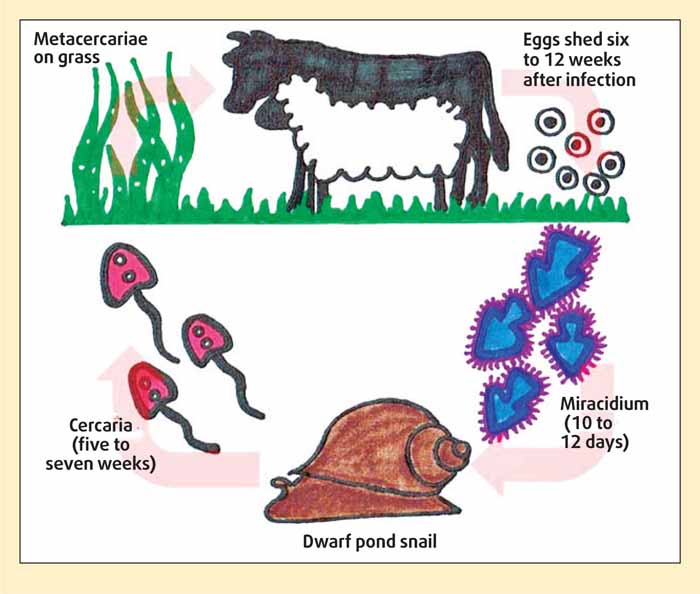

In comparison to other internal parasites, the life cycle of the liver fluke is complex since it involves many larval stages and must also pass through a snail intermediate host (Figure 1).

In the UK, the most common species of snail is Galba truncatula, the dwarf pond snail. These snails feed on algae found on the surface of mud and prefer areas of slow moving water with a neutral pH. They are normally found on mud on the margins of ponds, streams and poached ground. Therefore, disease is more prevalent in the wetter parts of the country. Due to hibernation of the snail and interruption of the fluke life cycle during the winter, disease is seasonal, with August to October being the peak times.

The severity and duration of disease depends on the numbers of fluke present and the age and immunity of the animal. There are different forms of disease – acute, subacute, chronic and subclinical. Which form occurs depends on the numbers of infective metacercariae ingested and the period of time over which they have been consumed.

In dairy cattle acute disease is rare and the subclinical stage is the most common, with lower milk yields, poor reproductive performance and an increased susceptibility to metabolic disease due to compromised liver function.

Treatment and control

Control strategies must be considered not only on a farm-by-farm basis, but also year on year, since the risk and also the timing of potential disease will vary. All factors associated with infection must be considered, including other animals on the farm (particularly sheep), history of the herd, the level of challenge and possible wildlife reservoirs.

While flukicides are important in controlling disease, other management practices can be put in place to reduce the infection pressure through reduction of snail habitats and/or access to them.

If permanent snail habitats are known, for example, around ponds and waterways, then these can be fenced off from livestock or livestock kept off the wettest fields in the autumn and winter. Snails will also form temporary habitats in areas liable to flood and even in and around muddy gateways and feed troughs, therefore draining land, maintaining gateways and moving feed troughs before the surrounding area becomes poached are all helpful in reducing snail numbers and infection levels.

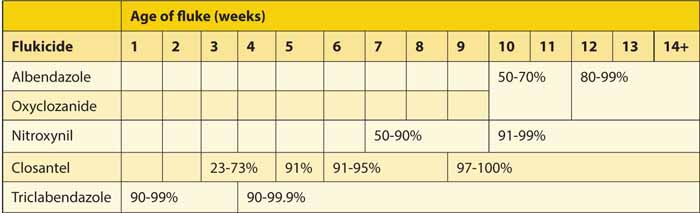

When choosing an appropriate flukicide it is important to take into account the fluke forecast and consider the stages of the life cycle that will be present at the time of treatment. For example, if animals have been housed for a period of time, then don’t treat for all larval stages when it is likely only adults will be present. Most flukicides on the market are effective in the treatment of chronic liver fluke since they treat adults; however, not all treat all larval stages (Table 1).

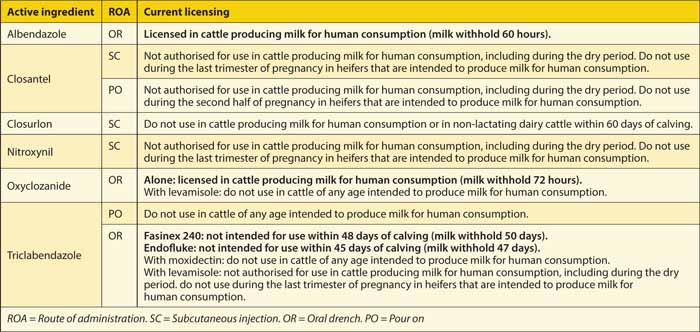

Following the European Commission regulation changes in July 2013 regarding the use of some flukicides in animals producing milk for human consumption, the treatment choices for dairy cattle are somewhat limited. This is due to a lack of maximum residue limits (MRLs) for milk for closantel, clorsulon, nitroxynil and triclabendazole (excluding Fasinex 240 and Endofluke).

The current regulations regarding the use of flukicides in dairy animals is given in Table 2; however, since these are liable to alter as MRLs are determined for the various flukicides, it is important to continually check the most recent data sheets.

Currently, the only products licensed in lactating dairy cattle treat adult fluke only and are albendazole (60-hour milk withhold) and oxyclozanide (72-hour milk withhold). Fasinex 240 and Endofluke may be used at dry-off; however, milk for human consumption can only be taken from 50 days and 47 days following treatment respectively.

Liver fluke treatment in dairy cattle must not focus on the use of flukicides alone and instead should involve a tailor-made approach considering all factors involved in infection on an individual farm.

The aim of the control plan must be the reduction of infection pressure rather than complete elimination of infection.

Unnecessary treatments can not only lead to resistance, particularly in the case of triclabendazole, but also be costly in terms of lost milk. Therefore, careful evaluation of the herd’s infection status is required before determining a treatment plan.

References and further reading

- McCann et al (2010). Seroprevalence and spatial distribution of Fasciola hepatica-infected dairy herds in England and Wales, Vet Rec 166(20): 612-617.

- Pritchard et al (2005). Emergence of fasciolosis in cattle in East Anglia, Vet Rec 157(19): 578-582.

- Williams D J et al (2014). Liver fluke – an overview for practitioners, Cattle Practice 22(2): 238-244.

- VMD/NOAH Flukicides Statement July 2013. www.cattleparasites.org.uk

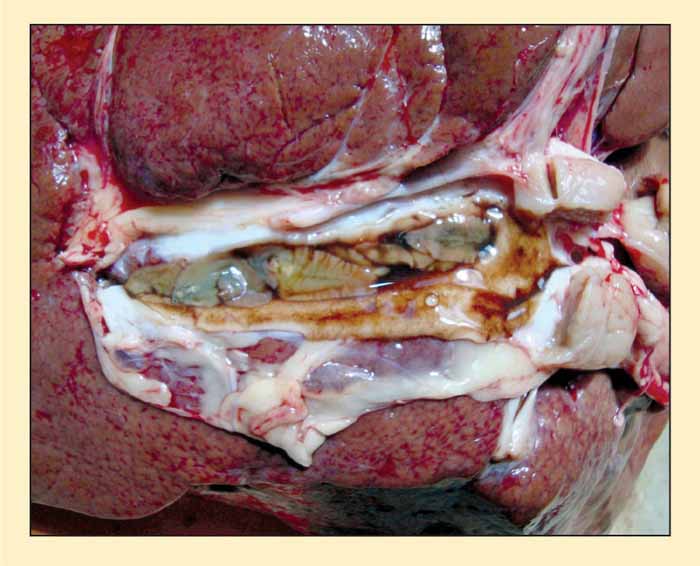

Figure 3 (below). Adult liver fluke present in bile ducts.

IMAGES: University of Liverpool.

Table 1. Stages of fluke killed by different flukicides and efficacy

Table 2. Summary of regulations regarding use of flukicides in adult lactating and non-lactating cattle and youngstock intended to produce milk for human consumption