12 Apr 2021

Taking a holistic approach to the care of geriatric dogs

Veterinary medicine is continually evolving and developing both in response to new technologies and medicines, but also to the changing structure and demographics of the profession and our patients.

One of the most striking changes that has occurred in the recent past has been the change in breed popularity and life expectancy. Average life expectancy of all dogs in the UK is 12 years (O’Neill et al, 2013), but this hides a wide variation from the longest lived breeds (miniature poodle, bearded collie, border collie, West Highland white terrier and miniature dachshund) averaging 13.5 to 14.2 years to breeds with short life expectancy such as the dogue de Bordeaux and great Dane (5.5 to 6) years.

Differences in longevity are also influenced by sex (female longer than males) and whether a pedigree dog is considered to be inbred (shorter) than outbred (longer). Other factors such as the likelihood of trauma (higher in cross-bred dogs; Yordy et al, 2020), cranial cruciate rupture or exposure to diseases such a leishmania (Pereira et al, 2020) also impact survival times.

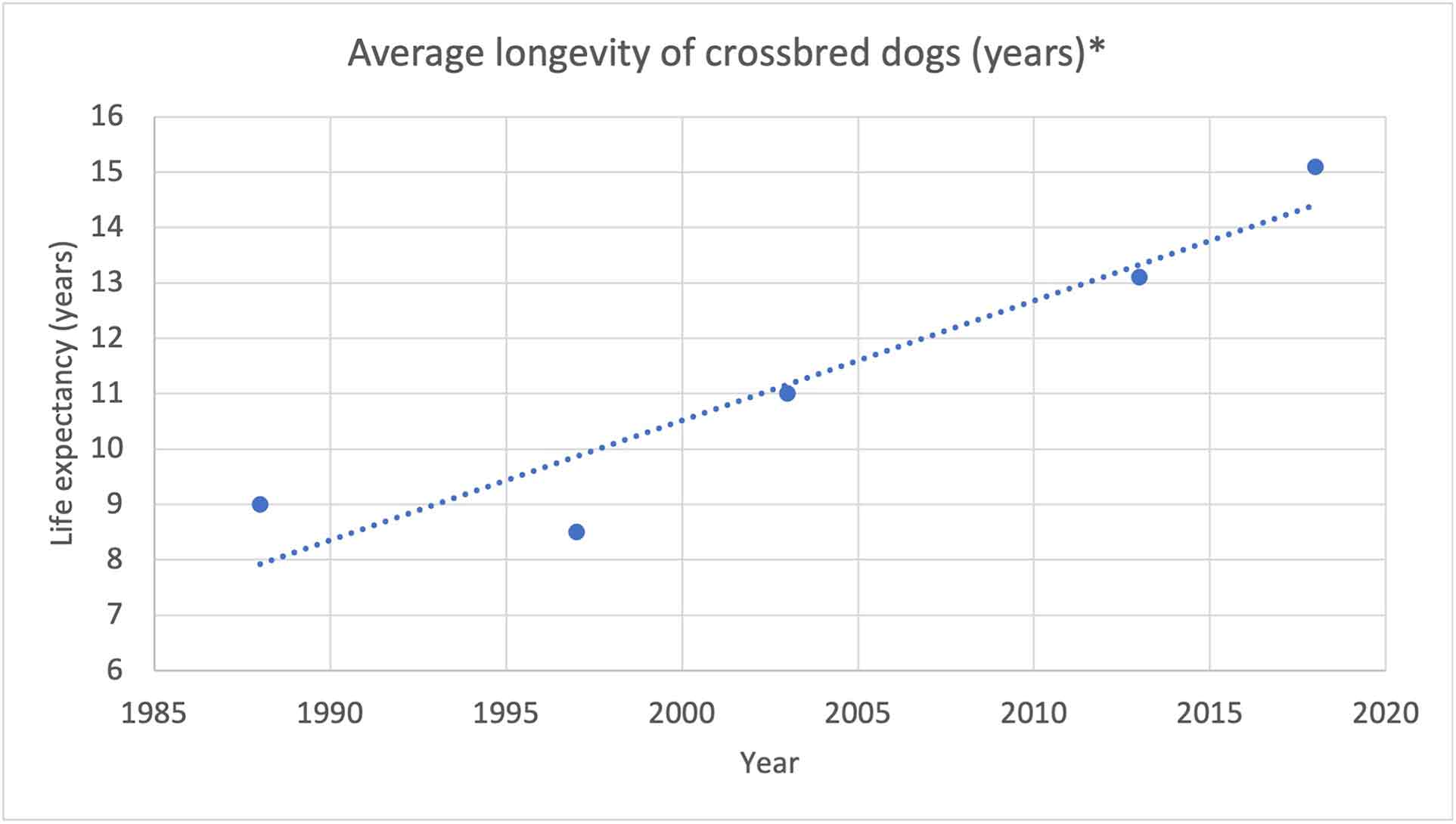

Average life expectancy does seem to be increasing and would predict that average life expectancy of cross-bred dogs would be around 15 years in 2021 (Figure 1). The impact this has on veterinary care is seen by many consultations moving away from acute medicine and surgery to managing elder dogs that often have multiple comorbidities that are non-resolvable and progressive; for example, 30% of small-breed dogs older than 10 years of age have significant cardiovascular disease.

The impact of age, lifestyle, body condition and disease will affect all major organ systems, including the nervous system, with gradual loss of sensory ability and progressive cognitive dysfunction. Of a thousand recent canine referrals to the author, 36% were older than 10 years of age and the majority of these had more than one chronic problem.

Many owners of elder patients are less keen for major investigations or interventions, but still want to improve the quality of life of their pet. This means that the care pathway becomes more of a conversation between the veterinary professionals involved and the owner to decide on the best approach to trying to define the problem(s), and then developing a holistic care plan for that individual.

The more problems an individual has, the greater the importance of recognising the complex interactions between the various conditions present and the drugs that are being used to manage them. Unfortunately, the majority of the veterinary literature is devoted towards single disease entities and very little to how best to manage a group of comorbidities, not least because the potential combinations are vast, making it challenging to identify a homogeneous cohort to study.

This leaves us with taking the information available on each individual disease, and blending them together using our professional experience and judgement, and then auditing the response of an individual against an agreed plan. Such an approach provides a real challenge to the veterinary team in terms of the time resource required to discuss with the owner the problems that are affecting their dog, the diagnostic plan, therapeutic solutions, goals and follow-up.

Goals become particularly important in these cases as most of the conditions will require management rather than be amenable to cure and, hence, agreeing criteria for successful management is critical.

Because of the complexity and variety of potential presentations and disease combinations, taking a case example to illustrate the process helps provide clinical relevance and practical detail. In essence, caring for geriatric patients requires an individual care plan with targeted diagnostics and therapeutics (often including diet and environmental change) that, to be successful, requires owner buy-in and involvement.

Presentation and history

You are working in a practice with 15-minute appointments and your next case is a 13.09-year-old male, neutered cavalier King Charles spaniel, Woody (Figure 2) for a heart check-up. He was diagnosed with a grade II, left apical, mid-late systolic heart murmur 18 months previously. On his most recent check, 6 months ago, the murmur was graded as III and pansystolic.

On presentation today the owner reports that Woody is quieter than normal, less keen to exercise and sleeping more during the day. The owner has also noticed a lump developing over his left ribcage. Taking a full history, the owner also reports that Woody’s appetite is less good, although he has not appeared to lose weight, and there are times when he is reluctant/unable to jump into the car.

Further, when out on walks, Woody sometimes does not seem to respond to calling, appearing deaf, and at other times he appears a little confused. The owner also reports that Woody is restless at night and occasionally urinates in the kitchen, even when he has only been left for a short time, which is very unusual for him.

Physical examination

Physical examination reveals a heart rate of 138bpm with a regular synchronous pulse and a grade III to IV/VI left apical pansystolic widely radiating murmur. Moderate dental disease exists, with some tartar and gingivitis, as well as grade I patella luxation bilaterally and hip discomfort. Ophthalmic examination shows mild nuclear sclerosis, but is otherwise unremarkable.

The lump on the thorax feels soft, fluctuant, well defined and SC approximately 25mm × 15mm; a fine-needle aspiration biopsy (FNAB) has a greasy texture. A plan is agreed with the owner for a 30-minute video call to discuss the results and options for further investigation. In-house cytology of the FNAB is consistent with a lipoma.

Plan for Woody

Discussions with the owner are centred around quality of life, risks, benefits and costs of treatment. Based on the physical examination, many of the issues described by the owner could be explained by the known problems – orthopaedic pain, and dental and cardiovascular disease.

While in a crude clap test Woody did respond, sensory loss could be responsible for his confused behaviour and lack of response to calling, but equally this behaviour could be due to metabolic or neurologic disease.

It was agreed that Woody’s dental disease was significant, but that it was hard to assess the anaesthetic risk without some investigation to assess the status of his (presumed) myxomatous mitral valve disease and exclude metabolic causes of some of his signs.

The owner decided on an initial investigation with routine haematology and biochemistry, and opted for a focused echocardiogram to stage the mitral valve disease rather than N-terminal pro-brain natriuretic peptide to assess volume loading of the heart.

Results of initial investigation

Mean systolic blood pressure measured by Doppler was 125mmHg (ref: 120 to 150). Blood sampling showed a mild leucocytosis of 17.6×109/L (ref: 6 to 15) with a neutrophilia 14.3×109/L (ref: 3 to 11.5; thought most likely to be due to dental disease), mild elevation in liver parameters (alkaline phosphatase 157iU/L; ref: less than 50, alanine aminotransferase 40iU/L; ref: less than 25, Gamma-glutamyltransferase 7iU/L; ref: less than 27, glutamate dehydrogenase 4iU/L; ref: less than 10), but pre-prandial and postprandial bile acids within the expected reference interval.

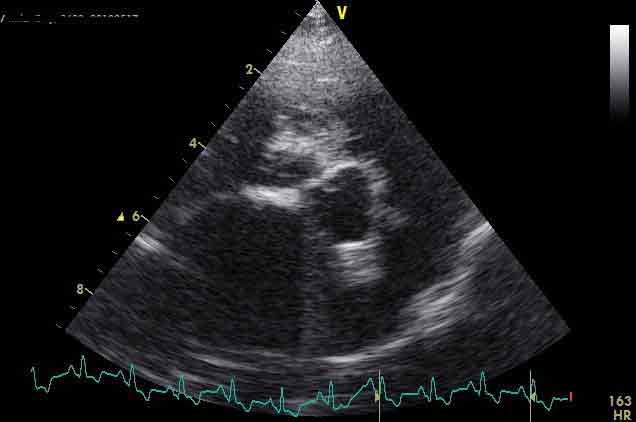

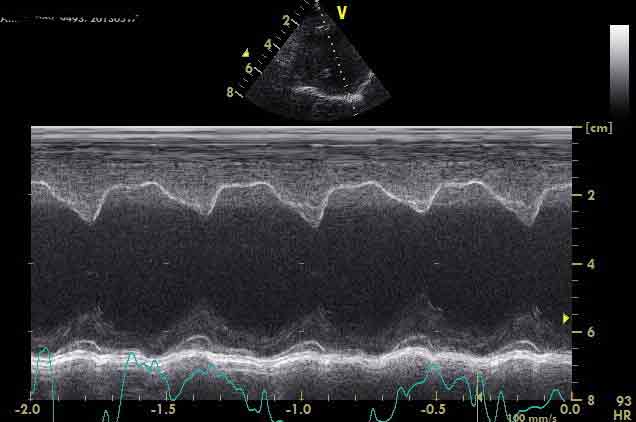

Urea was 10.2mmol/L; ref: 2 to 9 and creatinine 130µmol/L; ref: less than 125. Assessment of the normalised left ventricular diameter in diastole as per EPIC study (Boswood et al, 2016) was 2.4 and left atrial to aortic ratio 2.2 (Figures 3a and 3b). Based on these results, pimobendan therapy was started at 2.5mg by mouth every 12 hours.

Next steps

At a three-week follow-up telephone conversation, the owner reported that Woody was exercising better, and was perhaps a bit brighter and more alert, although he remained restless at night with occasional ”accidents”.

Anaesthesia for dentistry and a hip radiograph was agreed and undertaken the following week; the owner supplied a morning urine sample for testing that showed a urine-specific gravity of 1.020, pH 6.5, trace of protein and an inactive sediment. Anaesthesia was uneventful, with Woody maintaining a reasonable blood pressure throughout the procedures receiving conservative fluid therapy (3ml/kg/hr). Radiographs of his pelvis showed mild to moderate hip dysplasia with secondary OA.

Options to manage the pain associated with his OA were discussed, taking into account the likelihood that Woody had early chronic kidney disease (International Renal Interest Society; stage II) and stage B2 myxomatous mitral valve disease.

Use of NSAIDs was discussed in respect of the renal changes demonstrated and the concerns in humans about their use in patients with reduced left ventricular function (Schjerning et al, 2020). On balance, it was felt that NSAIDs were likely to provide a good level of pain relief, improving Woody’s quality of life, and that the risk profile was acceptable with an initial recommendation that renal parameters were rechecked in three to four months’ time.

Three weeks later, the owner reported that they now considered Woody’s exercise tolerance to be normal and that he was generally brighter, with a return to a normal appetite. However, concern remained over the behavioural changes, which, if anything, had become more pronounced over the past two months. The owner did not feel that they wanted Woody to have further investigation at this stage.

Discussion

Woody has a number of degenerative comorbidities that are not resolvable, but management seems to have produced a significant improvement in his quality of life. However, it has to be recognised that there is the potential for a significant placebo effect in owner reporting of general well-being, exercise and appetite. Although some objective measures could potentially be used, such as an activity tracker, we are largely reliant on owner reporting of improvement.

In discussion with the owner, it was felt that many potential causes of Woody’s behavioural changes had been excluded and that cognitive dysfunction was likely. The owner was keen to know more about this syndrome and to consider trial therapy as long as it carried low risks of side effects and was unlikely to impact on Woody’s other identified problems.

Cognitive dysfunction

Cognitive dysfunction (CD)is a neurodegenerative disorder of senior dogs and cats characterised by gradual cognitive decline and increasing brain pathology, with patients becoming less able to perform a variety of tasks and losing some of their learned behaviours.

With age, the brain atrophies, with a decrease in total weight and size. Numbers of neurons decrease while glial cells increase. These changes compromise blood flow and glucose utilisation, and result in hypoxia. Increased accumulation of β (beta) amyloid occurs secondary to numerous vascular and perivascular changes that occur, including microhaemorrhages and infarcts (Head, 2011).

β amyloid is considered a neurotoxic protein with the degree of accumulation associated in a number of studies with the severity of cognitive decline.

Diagnosis of CD is by exclusion of other causes and, although not exhaustive in Woody’s case, the clinical presentation, test results to date and response to treatment supported a presumptive diagnosis of CD.

Prevalence rates are high in studies looking at CD, with 28% of 11-year-old to 12-year-old dogs and 68% of 15-year-old to 16-year-old dogs showing at least one sign consistent with CD compared to around a 2% diagnostic rate by clinicians.

While most studies looking at specific conditions tend to find a higher prevalence than is diagnosed in practice, the difference is marked and does suggest a significant level of under-recognition in general practice.

Multiple therapeutic approaches have been used to manage CD, with evidence that some are efficacious in dogs (Dewey et al, 2019). Diets containing mitochondrial cofactors, essential fatty acids and medium-chain triglycerides have been shown to improve cognitive task performance, with S-adenosyl methionine also having been associated with reduced clinical signs of CD.

Environmental/cognitive enrichment (for example, social interactions, regular exercise, introduction of new toys) can improve cognitive function and delay cognitive decline, and provides additional improvements over diet alone. Medical therapy with selegiline at 0.5mg/kg to 1.0mg/kg by mouth every 24 hours showed benefit in one study in 77% of dogs.

A wide variety of other therapies have been used, aimed at calming the patient, reducing anxiety and normalising the sleep-wake cycle, including melatonin, valerian root, dog-appeasing pheromone, phosphatidylserine and ginkgo biloba; evidence of efficacy is limited.

In Woody’s case, the owners felt dietary therapy combined with environmental enrichment (“play dates” with other dogs and regular training while out on walks) reduced the nocturnal unrest and improved response when out on walks.