25 Oct 2022

Physiotherapy’s place in managing chronic pain in cats and dogs

It is stated by law under the Animal Welfare Act (2006) that we should provide support and reduce pain within our patients, keeping them as comfortable as possible in our care. Working within the veterinary profession, animal welfare is at the forefront of all care.

Assessing and alleviating any form of pain should be part of our care and ethical responsibility. The International Association for the Study of Pain defines it as “an unpleasant sensory and emotional experience associated with actual or potential tissue damage”.

Firstly, when we look at pain as a whole in medicine, we then need to look at the process and mechanisms, along with understanding the difference between acute and chronic pain.

Pain itself could be solely discussed as a subject when identifying the complexities, physiologies, and mechanisms through the tissues and nervous systems. Pain is described as nociceptive pain, or pain that has arisen from activation of nociceptors; this may be through actual or threatened damage to non-neural tissues.

Chronic pain is identified as pain that persists for three months or longer, and is considered to have an underlying disease process; the chronic pain patient generally doesn’t present in a similar way to the acute pain patient due to the pain mechanisms and the prolonged response and mechanisms.

Panel 1 provides examples of common conditions faced in veterinary practice on a daily basis and whether they would identify as chronic or acute.

Acute pain

- Fracture

- Wounds – abrasion, wound minor cuts

- Post-surgery

- Sprain or stain

Chronic pain

- Arthritis

- Neoplasia

- Endocrine disease

- Musculoskeletal – spondylosis, dysplasia

When caring for animals, we understand communication is limited, and this includes making us aware of pain while also considering their own survival techniques as a species to potentially protect themselves from other predators or species.

Animals communicate to us through behaviour and other physical displays, which could also become breed-specific or even specific to the an individual when displaying signs of pain (Grant, 2006). In relation to the behaviours that may be key signs, pain scoring systems can be implemented, along with other forms of clinical assessment and communication with the owner.

Pain scoring systems have become routine practice in veterinary medicine and allow veterinary professionals across the board to have an understanding of a patient’s condition, ability and pain.

While pain scoring systems could still be seen as subjective and potentially not a good method of data collection, they do hold value when working within busy practices with multiple staff members or potentially different teams, such as out-of-hours, kennel staff and rehabilitation units.

Pain scoring enables recognition of pain by veterinary professionals, which then allows the appropriate course of treatment to be prescribed along with staff quantifying the pain itself and recognising whether the prescribed treatments are having the desired effect on the patient and alleviating the pain.

Mathews et al (2014), in the WSAVA guidelines, described pain as “a complex multidimensional experience involving sensory and affective (emotional) components” – in other words, it is not just about the sensation, but about how it would make one feel, which ultimately is our challenge when working with animals. Irrelevant of a specific method of pain scoring, it is carried out via collecting data from specific signals – these include:

- Crying – vocalisation of any kind, taking into account normal behaviours, environment and response to a stimulus. For example, examining a specific site.

- Facial expressions – ear position, eye shape, pupil size and general facial response.

- Body posturing – positioning, movements and response in body shape. For example, hunchback, head holding and paw placement.

- Physiological factors – heart rate, respiratory rate and temperature.

- Behaviour – change in behaviour and understanding with a good owner and professional discussions.

Overall considerations into whether the patient has any other clinical conditions or could potentially be a candidate with multiple health concerns should always be considered when assessing and making a clinical analysis (Mathews et al, 2014).

Pain relief

Once the patient’s pain has been established, generally the next route would be to prescribe and try to reduce pain, and provide the patient with adequate pain relief.

In veterinary medicine, the common drugs prescribed would come with pharmacological groups such as opioids, NSAIDs and corticosteroids.

Chronic pain is almost considered a disease state, as pain due to its longevity and reduced rate of healing or potential inability to heal. Acute pain usually is approached by treatment of the underlying cause and interrupting nociceptive signals, whereas chronic pain requires a multidisciplinary approach and ideally should involve more than one modality of treatment.

As veterinary medicine is fast developing and following close behind human medicine with methods of treatment, alternative therapies are being widely used as another add-on to help relieve pain and improve quality of life.

Musculoskeletal pain is one of the most stubborn types of pain and can be distressing for patients, along with having progressive – and in some cases devastating – consequences if not managed.

Veterinary professionals are starting to consider other therapies, including physiotherapy, as part of the treatment plan for their patients. Physiotherapy has a multidimensional effect through providing relief to the primary stimuli, such as acute pain associated with post-surgical cases, fracture repair or injuries, or the secondary compensatory issues associated with arthritis and chronic conditions by improving well-being and activating the patient through other physical and mental ways having a positive effect.

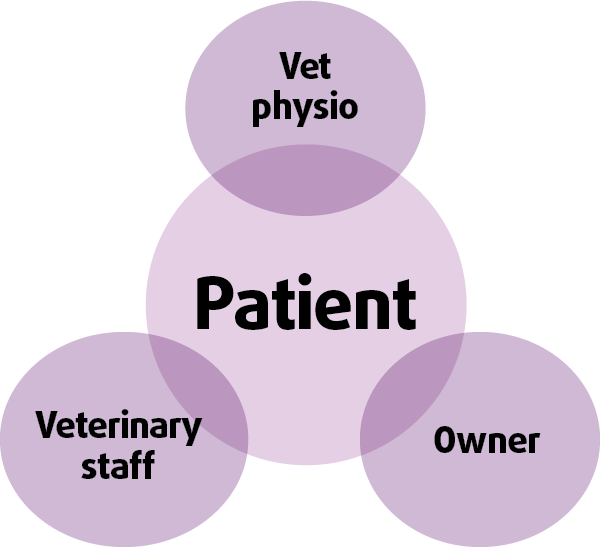

Figure 1 demonstrates the overlap between the owner, vet and therapist, who all need to work together to deliver optimum results.

Physiotherapy

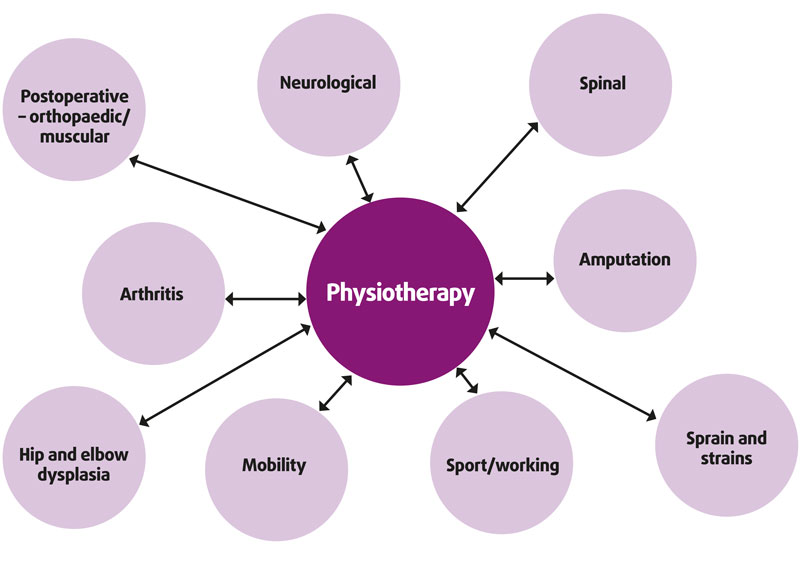

Physiotherapy – also known and referred to as physical therapy – evaluates function and movement with the aim to optimise the physical potential of the patient (McGowen et al, 2007). The objective of physiotherapy is to promote healing, maintain or increase muscle strength, reduce pain, and increase joint health and range of movement (ROM), while taking into account an individual’s health status (Hodges and Mosely, 2003; Figure 2).

In human medicine, physiotherapy is acknowledged as a method of treatment, and the physiotherapist is respected and understood with their professional status and qualifications. This is currently the aim within the veterinary profession when trying to establish protection of status and title, which makes it clear on a therapist’s qualifications and remit of practice.

The process of assessment in a physiotherapy session involves:

- assessment of the musculoskeletal system, including conformation, joint ROM, abnormalities and suspicion of chronic conditions

- musculoskeletal, including mass, abnormalities affecting movement and biomechanics

- neurological systems – including proprioceptive deficits, pain response or lack of – carried out with various observations looking at posture and gait (Levine et al, 2005).

The full assessment is required to identify the musculoskeletal abnormalities or why impaired function may exist and where it originates from (Goff, 2009).

When comparing a veterinary physiotherapist to a veterinary surgeon, while similar, they differ with some aspects, but equally align with the same clinical goals of assessment, treatment and improvement of quality of life. The veterinary physiotherapist will look at functional aliments/impairments, and identify existing or potential issues, while also looking at activity, performance, weakness or disabilities that impact biomechanics, whereas the veterinary surgeon approaches clinical cases looking for a pathological diagnoses, which explains the patient’s clinical condition, abnormalities and why it occurs.

Once the physiotherapist has assessed the patient, treatment is carried out via manual massage, passive or active movement techniques, thermotherapy, cryotherapy, exercise, myofascial release, trigger point management and electrotherapies.

Evidence base, while currently limited in veterinary physiotherapy, can be seen through human medicine and numerous supportive papers on physiotherapy rehabilitating a range of clinical conditions – Krebs et al (2000) demonstrated physiotherapy in the support of injuries to the shoulder, forearm and wrist, while Richardson et al (2002) demonstrated its use in the prevention of pelvic pain and Hodges et al (2003) with back pain.

Common conditions seen in small animal medicine that require rehabilitation similar to human medicine also demonstrated smoother recovery with rehabilitation plans with cases of cruciate rupture (Anderson and Lipscomb, 1989; Shelbourne and Nitz,1990; Shelbourne and Gray, 1997), arthritis (Dias et al, 2003) and fracture repair (Sherringon et al, 2003).

In an evidence-based profession, it is completely necessary to consider research available when making any decision on patient care and it is clear physiotherapy can make a difference.

Referral process

As educational sectors in veterinary medicine try to educate future professionals in the importance of rehabilitation and the multidisciplinary approach to treatment of vast clinical cases, a gap within the profession and uncertainty still exist when referring cases.

The physiotherapist will request referral from the treating veterinary surgeon, which allows the therapist to have a full clinical background that should be as specific and detailed as possible, along with making the therapist aware of any other health concerns – for example, heart conditions, or respiratory or endocrine issues that could have an impact on modalities used, methods of treatment or the overall approach to the patient’s treatment plan.

The physiotherapy assessment should work alongside the veterinary surgeon’s assessment – potentially finding other pieces of the puzzle to either assist in treatment and/or refer back to the veterinary surgeon when finding issues associated to the primary condition or other that the patient was referred for, or other contributing factors.

Physiotherapists have time on their side, with usually 45 minutes to 1 hour-plus in the initial assessment, allowing a therapist to take their time when assessing anatomical structures and the mechanics in a calm environment.

In any uncertain situation, communication is key and it should be considered that referral may be concerning when giving permission for another professional to treat ones patient with no history or relationship prior to this. The relationship should be professional and positive between the veterinary practice and the veterinary physiotherapist, with good communication between professionals, providing the optimum care and treatment for the patient and client, along with a professional trust.

A fully qualified physiotherapist should be qualified and registered, with this easily accessible when double checking status, and the therapist should have clear registration status and qualifications. Client and patient care are of great importance, and progression in clinical status should always be a priority, which is why considering physiotherapy in animals with movement abnormalities, degenerative disorders, injury, post‑surgery, arthritis or the numerous musculoskeletal disorders is vital, and is an added form of pain relief.

What clinical cases can be referred?

Many clinical conditions benefit from the use of physiotherapy and, as seen in Figure 3, patients seen on a daily basis would benefit from the therapy.

The species treated will also depend on therapist and clinical scope; with this, small animals such as rabbits and cats should not be ruled out, as we commonly think of our canine patients carrying out an exercise prescription or being the primary patients that would benefit.

The therapy itself includes a range of treatments and if certain treatments may not suit an individual, such as manual therapy (stretching/massage) in feline patients, then post-assessment other methods may be used such as electrotherapy treatments.

As a general rule, the majority of musculoskeletal, neurological and orthopaedic cases will benefit from physiotherapy and it should always be considered as another form of pain relief.

References

- Anderson AF and Lipscomb AB (1989). Analysis of rehabilitation techniques after anterior cruciate reconstruction, The American Journal of Sports Medicine 17(2): 154-160.

- Dias RC, Domingues JM and Ramos LR (2003). Impact of an exercise and walking protocol on quality of life for elderly people with OA of the knee, Physiotherapy Research International 8(3): 121-130.

- Goff L (2009). Manual therapy for the horse – a contemporary perspective, Journal of Equine Veterinary Science 29(11): 800-807.

- Grant D (2006). Chronic pain management and quality of life. In Pain Management in Small Animals: a Manual for Veterinary Nurses and Technicians, Butterworth-Heinemann, London: 293-310.

- Hodges PW and Mosely GL (2003). Pain and motor control of the lumbopelvic region: effect and possible mechanisms, Journal of Electromyography and Kinesiology 13(4): 361-370.

- Krebs HI, Volpe BT, Aisen ML and Hogan N (2000).Increasing productivity and quality of care: robot-aidedneuro-rehabilitation, Journal of Rehabilitation Research and Development 37(6): 639-652.

- Levine D, Millis DL and Marcellin-Little DJ (2005). Introduction to veterinary physical rehabilitation, Veterinary Clinics of North America: Small Animal Practice 35(6): 1,247-1,254.

- Mathews K, Lascelles D, Nolan A, Robertson S, Steagall P and Yamashita K (2014). Guidelines for recognition, assessment and treatment of pain, Journal of Small Animal Practice 55(6): 10-68.

- McGowan C, Stubbs N and Jull G (2007). Equine physiotherapy: a comparative view of the science underlying the profession, Equine Veterinary Journal 39(1): 90-94.

- Richardson C, Snijders CJ, Hides JA, Damen L, Pas MS and Storm J (2002). The relation between the transversus abdominis muscles, sacroiliac joint mechanics and low back pain, Spine 27(4): 399-405.

- Shelbourne D and Gray T (1997). Anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction with autogenous patellar tendon graft followed by accelerated rehabilitation. A two- to nine-year followup, The American Journal of Sports Medicine 25(6): 786-795.

- Shelbourne D and Nitz P (1990). Accelerated rehabilitation after anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction, The American Journal of Sports Medicine 18(3): 292-299.

- Sherrington C, Lord H and Herbert R (2003). A randomised trial of weight-bearing versus non-weight-bearing exercise for improving physical ability in inpatients after hip fracture, The Australian Journal of Physiotherapy 49(1): 15-22.