19 Apr 2021

No more lame excuses: why it’s time to stop failing lame cows

With one in three cows thought to be lame at any one time, clear strategies are needed, as the authors outline in this article.

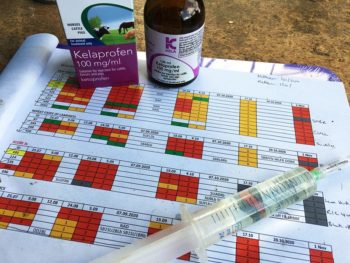

Figure 3. Treating new cases of lameness with a therapeutic trim, block and NSAID is recommended even if there is only perceived to be “mild” bruising. IMAGE: James Wilson

It has long been recognised that lameness is a major welfare concern and results in significant economic losses. However, the past few years have seen it rise to the top of the agenda. A survey by the Cattle Health Certification Standards Board highlighted lameness as the top welfare challenge facing vets and farmers across the UK (Westgate, 2020).

Research suggests that, on average, one in three cows is lame at any one time (Griffiths et al, 2018; Randall et al, 2019), with little evidence to suggest this is improving at a national level. It is clear that we need to look at our current strategies and ask ourselves if we are doing enough.

Why do cows go lame?

We can separate the main causes of lameness into claw horn lesions (non-infectious) and infectious lesions. Claw horn lesions are mechanically driven lesions of the hoof capsule (that is, sole bruising, sole ulcer and white line disease), whereas the infectious causes of lameness are driven by bacterial infections that affect the skin around the hoof.

It is important to differentiate between the lesions causing lameness on a farm so that a targeted approach to prevention can be taken through a structured programme, such as the Agriculture and Horticulture Development Board (AHDB) Healthy Feet Programme. For instance, there is not much point in a farmer investing in a fully automated footbath when sole ulcers are the main issue. For the purposes of this article, the focus will be on claw horn lesions.

Claw horn lesions

The development of claw horn lesions is primarily a combination of a failure of the internal anatomy of the hoof to protect the hoof capsule from damage and suboptimal management of cows at specific time points.

Role of calving in lameness

The suspensory apparatus and digital cushion (or fat pad) are crucial support structures for the pedal bone. Around calving, both are compromised, leaving the pedal bone less supported. Release of the hormone relaxin takes place, which results in weakening of the laminae that fixate the pedal bone within the hoof capsule, and also slackening of the tendons and ligaments that hold it in place.

At the same time, an increased mobilisation of fat takes place, as the cow rises to peak milk yield, and this leads to a reduction in the support provided by the digital cushion (Bicalho et al, 2009; Newsome et al, 2017a; b). It is a misconception that the digital cushion acts as a “shock absorber”, since the type of fats contained in the digital cushion dissipate rather than absorb forces. A digital cushion that has been compromised will have a reduced ability to dissipate the forces that occur during locomotion and standing from the vulnerable sole area of the foot, and to the stronger, weight bearing walls.

When we consider these changes also occur at a time when cows are likely to experience increased standing times on concrete due to factors such as a change in housing, introduction into the milking herd – which can lead to bullying (especially in heifers) – and long walking distances if grazing, it creates the perfect storm for the development of claw horn lesions.

The combination of changes in anatomy, and increased risk through management, create excessive pressure through the pedal bone on to the horn-producing corium that lies underneath. This results in haemorrhage, which is then incorporated into the horn as it grows and results in a visible sole bruise. In severe cases, horn production completely ceases, and a sole ulcer forms. The trauma to the corium also results in a substantial inflammatory response that is thought to cause further damage to the internal structures of the hoof, specifically the pedal bone (Newsome et al, 2016).

This then creates a vicious cycle of further injury to the corium and more inflammation, which further perpetuates pathological changes to the pedal bone and the path to a chronically lame cow forms.

But what about laminitis?

Historically, much emphasis has been placed on the role of acidosis, and more recently subacute ruminal acidosis, in the development of claw horn lesions. However, when laminitis is recorded as a lesion, it is more commonly a misclassification of sole bruising that we are seeing. The evidence base behind the “laminitis hypothesis” is also very weak (Randall et al, 2018a), and the trauma/inflammation pathway hypothesis is much more supported in the literature.

Get lame: stay lame

We now have a growing body of evidence that demonstrates that once a cow goes lame, she is predisposed to repeated cases of lameness for life. While this lameness may be intermittent and fluctuate in severity, the overall pattern is cows with a history of lameness are the key drivers of lameness prevalence on farm and contribute significantly to the number of lameness treatments undertaken (Randall et al, 2018b).

It is also clear that the longer a cow is lame, the less likely she is to respond to treatment (Groenvelt et al, 2014; Thomas et al, 2015; 2016), and that interventions such as preventive hoof trimming will be less effective in preventing future lameness (Daros et al, 2019).

If we identify cows at an early stage of lameness and treat them effectively then it has been shown we can improve a cow’s outcome (Thomas et al, 2015; 2016), and potentially halt the progression towards a chronically lame cow. This approach is called early detection and prompt effective treatment (EDPET). However, the reality is that it is rarely implemented correctly on farm. So, why is this the case and what can we do?

Failure to detect cases early enough

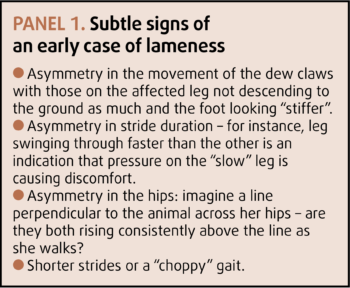

Mobility scoring remains the best tool we currently have to identify cows at an early stage of lameness. While there is, and will always be, a subjective element to mobility scoring through training, it is possible for almost anyone to recognise the subtle signs of gait change that indicate that early stage of lameness. By the time we wait for it to be obvious it is too late.

We need to stop focusing on the detection and treatment of end stage lesions such as sole ulcers and start to think of this as a failure of detection.

While intervening at an early stage can be challenging, it is proving to be more essential to try to prevent cows joining the pool of chronic cases. To be effective and identify cows that are going to benefit most from treatment we need to ensure that time is dedicated specifically to this task. It is often the best time to score as cows leave the milking parlour, but it is important to ensure they are not scored on rubber-matted return lanes or an area where their normal stride pattern would be affected, such as corners, slippery floors or slopes.

A shortened stride or asymmetry in the movement of the dew claws is often the earliest indication that a deep bruise is developing and that intervention is needed (Panel 1). It can be easy at this point to give the cow the benefit of the doubt, or think it isn’t that bad. However, that helps no one – least of all the cow.

When it comes to how often we should mobility score, the answer is the more often the better. However, current best practice recommendation would be fortnightly. The longer the interval between scoring, the longer the cow has potentially been lame for – and the lower the chances of a good outcome following treatment. With each day a cow is lame costing £2.20 (AHDB, 2021) it means a lot is at stake if treatment is delayed.

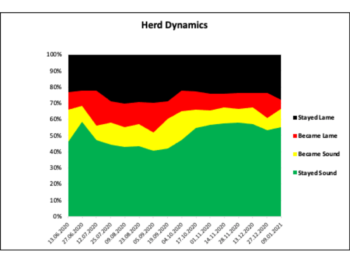

As well as being an integral part of EDPET, fortnightly scoring also provides us with invaluable data to allow tracking of trends, assess whether interventions are working, and also assess the effectiveness of treatment and preventive trimming (Figure 1). Combining this with the trimming records allows us to identify how effective early detection is; for instance, a high prevalence of sole ulcers and wall ulcers would indicate a failure in detection.

Alongside analysis of the mobility scoring data is also the opportunity to bring added value by recording other information, such as digital dermatitis scores, body condition score (BCS), hock lesions and more. If you are scoring during milking then it may also be possible to assess stockmanship as cows are brought to the parlour, standing times for milking and whether the backing gate is used correctly. Farmers can sometimes feel that mobility scoring doesn’t offer “value for money”. However, early detection is an essential component of managing lameness on farm, with a huge potential return on investment.

Failure to treat effectively

Mobility scoring alone, no matter how frequent, won’t address a lameness issue unless the results of the mobility score are acted on, but it must be done promptly. It is really important to ensure that when scoring is carried out, coordination takes place between the mobility scorer and either the external hoof trimmer or the in-house trimmer to ensure new score 2 cows are treated within 48 hours. Severe (score 3) cases need to be treated as soon as possible after identification, whether this be at a mobility score or at in-between scores. It is important the trimmer has both the scores and previous treatment history available when inspecting cases (Figure 2).

As well as being detected early and treated promptly, it is vital treatment is effective. It is important claw horn lesions are treated with a block, therapeutic trim and NSAID, as this will significantly improve the cows’ chances of recovering (Thomas et al, 2015), even if “only” mild bruising is noted (Figure 3). In some cases where lameness detection is very good, it is possible to identify lameness at the deep-bruise stage, even before haemorrhage is visible in the sole horn. In these cases, it can be easy to miss a cow that requires treatment; however, hoof testers are an essential piece of kit that should be used routinely to ensure this doesn’t happen (Figure 4).

While the use of therapeutic trimming and blocking has been established for many years, the use of NSAIDs in lameness is a relatively newer concept in comparison. However, good evidence demonstrates their benefit in early cases (Thomas et al, 2015; 2016), with further results from an additional randomised treatment trial expected later this year. The benefit seen with the addition of NSAIDs is thought to be two-fold; firstly, it provides pain relief for what is a painful condition, and secondly the dampening down of local inflammatory pathways in the foot reduces the impacts of pathological changes to its internal anatomy.

When it comes to treating lameness cases, it is also important attention is paid to block selection and block placement. Correct sizing of the block is important to ensure it protects the heels, but correct placement is also key to ensure it neither rocks in or out as the cow walks. Lesions should also be trimmed out sufficiently following the principles of the Five Step Method, with lowering of the heel on the affected claw and removal of all loose horn around the lesion. Extra time and attention here reaps rewards later on.

Prevention better than cure

With lameness levels still unacceptably high, alongside the promotion of EDPET it is also crucial we work towards prevention of lameness in the first instance. Claw horn lesions are more often than not the result of mismanagement of animals at critical time points in their lactations; predominantly around transition. We need to focus on enabling the cow to cope with the demands exerted on her during this period at a time when the anatomy of the foot is undergoing considerable changes, too.

We need to ensure that appropriate trimming regimes (and technique) are in place; BCS is maintained; and she is able to lie down for as long as she wants, when she wants, in a clean, comfortable bed. A lame cow should be seen as a failure in the system, and the key is to identify the risk point and control it through improved management.

Summary

It is clear that, with lameness levels still unacceptably high across the UK herd, we need to do better. We already have the evidence and tools to help drive this change, but attention to detail is needed. We need to detect earlier, treat promptly and treat effectively. Most of all, we need to monitor and identify the key targets for preventive measures. No silver bullet is available to tackle lameness, but – however hard – we need to tackle it, for the sake of the industry, but most of all for the cow.