20 May 2019

Good practice in dairy lameness: treatment aligned with research

Sara Pedersen looks at studies into the prevention and treatment of this condition, and applying it to veterinary practice.

Image © Sorensen / Adobe Stock

Lameness continues to be an ongoing challenge for the UK dairy industry. Despite repeated studies showing it is possible to achieve very low levels of lameness, the reported average prevalence remains unacceptably high, at approximately 30% (Griffiths et al, 2018; Randall et al, 2019).

Historically, the evidence base surrounding lameness has been relatively small given its importance; however, we now have a rapidly growing evidence base to support both the prevention and treatment of different causes of lameness.

Social media: friend or foe?

Despite having more evidence with which we can tackle lameness on farm, challenges still exist in disseminating the key messages. A key barrier continues to be the underestimation of true lameness levels within the herd, which does not help in creating the required motivation or belief that change is required.

However, for the farmer who does want to make changes, or look to the latest ideas for prevention and treatment, a new challenge now faces us in the form of social media. The rapid growth of social media, and particularly groups focused on feet, is a double-edged sword. While this provides a good forum for discussion, and promotion of research findings and best practice, it can also have a negative effect. In some instances, evidence-based treatments or approaches may be rebuffed in favour of popular opinion, despite a lack of evidence, leading to suboptimal or even detrimental outcomes for individual cows. vets

At a time when the industry is under great scrutiny, it is vital we continue to add to the evidence base surrounding lameness, but, crucially, that when key research findings emerge, these are disseminated widely to all stakeholders to make sure best practice is followed for the benefit of the individual cow, as well as the industry as a whole.

Prevention

Hardest risk factor to tackle

When it comes to tackling lameness, multiple risk factors exist; however, some are easier to deal with than others. While the farmer can control a herd’s future, he or she cannot change its past – on some farms this can have a large impact on the success of any interventions. A previous case of lameness has long been identified as increasing a cow’s future risk of a repeat case. Therefore, highlighting the impact of interventions on the incidence of new cases, instead of all cases, can often prove to be more motivating when it comes to monitoring progress.

A study by Randall et al (2018) sought to determine what proportion of overall lameness risk could be attributable to a previous case of lameness – that is, how important is a previous case of lameness when it comes to the risk of a future case? The longitudinal study looked at two different herds; records for the first herd (724 cows) were assessed over an 8-year period and data from the second herd (1,040 cows) over 44 months. The study found approximately 80% of lameness cases could be attributed to a cow having had a previous case of lameness. The results confirmed repeat cases contribute overwhelmingly to the total number of cases identified.

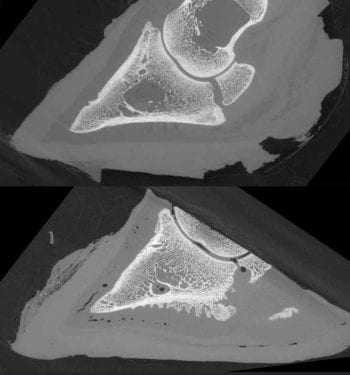

While preventing lameness in the first instance must remain the key focus of any lameness reduction plan, greater understanding is required as to why repeat cases occur and how these, too, can be prevented. In the case of claw horn disruption lesions (CHDLs), the development of new bone on the pedal bone is hypothesised to contribute towards the increased risk of a cow becoming lame again (Newsome et al, 2016; Figure 1).

Further research is taking place into new bone formation as a result of claw horn disruption lesions, and whether this can be prevented through alternative treatment protocols.

These studies highlight important messages that should be communicated to farmers when we are tackling lameness so they do not become despondent when improvements do not rapidly occur. When analysing records and reporting on progress, looking at new and repeat cases separately, as well as overall herd prevalence, can be a useful way of monitoring improvements and providing further motivation.

Looking to the future

When it comes to discussing lameness, the focus is often on the adult cows, with comparatively little time spent on the heifers. When a herd is breeding its own replacements, minimising lameness in heifers can result in long-lasting benefits when they enter the milking herd.

Heifers with more severe CHDLs at the time of first calving have an increased risk of lameness in the long term (Randall et al, 2016) and the reported high prevalence of lesions in first lactation heifers (Maxwell et al, 2015) means management during the rearing period, especially in the pre-calving period, should not be overlooked when considering herd control.

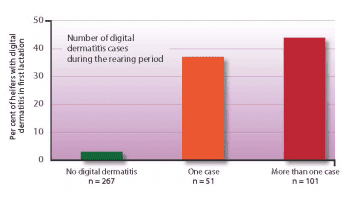

The impact of digital dermatitis (DD) during a heifer’s rearing period has also been highlighted in a study by Gomez et al (2015). Only 3% of heifers that did not experience a case of DD before first calving went on to have a case in first lactation. However, this rose to 37% for heifers diagnosed with one case during the rearing period and 44% for those that had more than one case (Figure 2).

This also had an impact on productivity, with heifers experiencing more than one case during the rearing period producing significantly less milk (335 litres per lactation) and taking longer to get back in calf (an extra 24 days) in comparison to heifers that had not had DD before first calving. Again, this points to the rearing period as being important in influencing lameness in the milking herd. When analysing records, assessing lesions by lactation can be a useful indicator of knowing where to target efforts.

Treatment

DD

Finding the ultimate cure for DD (Figure 3) has led to a plethora of products and concoctions being produced and marketed in the absence of any robust randomised trials to back up their claims. In some instances, treatments appear to be almost experimental, with their safety for the user, animal, environment and consumer often unknown.

Despite DD being a herd level problem, cases need to be treated at the individual cow level. Where a high proportion of the herd is affected, “blitz treatment” – that is, the simultaneous treatment of all cattle with active lesions – offers an effective way of rapidly reducing infection pressures in the herd. When treatment is followed by effective preventive measures, including footbathing and improved hygiene, long-term control becomes more achievable (Pedersen, 2019).

The aims of treatment are to quickly resolve the infection while minimising pain to the cow, reducing the risk of further encysting of the bacteria and ensuring antimicrobials are used responsibly. Our knowledge of the epidemiology of DD demonstrates it is highly likely the treponemes have already encysted in the skin by the time a lesion is identified for treatment. If we compare DD to the treatment of treponeme infections in humans (syphilis and yaws), it is likely a true bacteriological cure will only be achieved through very high antimicrobial doses for a prolonged period of time (Evans et al, 2016), which is impractical in a farm setting. Therefore, the primary aim in many cases is to resolve the secondary infection that develops on the skin surface.

Despite some new, exciting and innovative products being researched (including an extract of wasabi), on balance, the available studies still point to licensed topical antibiotic aerosols as the treatment of choice. It is important to note that antibiotic powders, such as tylosin, lincomycin and erythromycin, are off-label and, therefore, should not be used.

When treating a case of DD, it remains best practice to lift the affected foot with the cow in a crush so the lesion can be cleaned and thoroughly dried before application of the topical antibiotic spray. It also allows for a more thorough inspection of the interdigital space. However, treating large numbers of cows through the crush can be prohibitive when tackling DD on farm. Until recently, treating in the parlour contravened Red Tractor rules; however, following a risk-benefit assessment, this restriction has been lifted. Regardless of where cows are treated, it is important a sufficient number of treatments are given to ensure lesions successfully progress to the healing stage where they are covered in a thick black scab and are no longer painful. For small lesions, one to two days of treatment may be sufficient; however, larger well-established lesions may need up to five to seven days of treatment.

Claw horn disruption lesions

While preventing cases of lameness in the first instance is obviously the primary goal, when cows do go lame the evidence is very clear that the best outcome is achieved through treating promptly and effectively. Where one action is carried out without the other (that is, delayed identification of lameness, but best practice treatment applied; or prompt identification, but suboptimal treatment), it can lead to disillusionment from farmers as they may not see the maximum return from their efforts. Therefore, it is essential cases of lameness are identified promptly and treated effectively (Figure 4).

Treat promptly

The longer a cow is lame before treatment, the longer a recovery she will have. It is well-documented farmers underestimate the true prevalence of lameness in their herd. They also tend to be slower to pick up lameness, with the result being some mildly lame cows may not be treated at all, and others only when lameness has progressed and they become very obviously lame.

Treating lame cows quickly and effectively is a key component of any lameness reduction programme, with fortnightly scoring followed by prompt treatment of new cases of lameness proven to reduce lameness at herd level (Groenevelt et al, 2014).

However, persuading farmers to implement this can be challenging. Where time is seen as a barrier, using independent mobility scorers can be beneficial, so it does not fall by the wayside during busy times. It is also particularly useful if treatment lists can be generated for the farmers – rather than simply providing a list of scores they then have to decipher themselves. Liaising directly with the in-house or external foot trimmer is also essential to ensure the correct cows are being presented, so feedback on the findings can then be given to the farmer and progress monitored.

A common misconception is that scoring fortnightly is too frequent and four to six-weekly scoring may be sufficient. However, the same beneficial results are not seen with longer inter-scoring intervals. Thomas et al (2016) showed when cows had been lame for six weeks or more prior to treatment, overall cure rates were considerably lower than if they had been lame for two weeks or less.

Treat effectively

A randomised control trial by Thomas et al (2015) investigating the differences between four treatments for CHDLs remains a landmark study. Cows were enrolled if they were lame at the fortnightly mobility score, having been sound for at least the two previous scores. Enrolled cows were randomly subjected to one of four treatment groups:

- group one – therapeutic trim only

- group two – therapeutic trim plus application of block

- group three – therapeutic trim plus NSAID (ketoprofen for three days)

- group four – therapeutic trim plus block plus NSAID for three days

Cows were re-examined at 35 days post-treatment and defined as either a sound cow (score 0) or non-lame cow (score 0 or 1).

Cows in treatment group four – which received combination treatment with a therapeutic trim, block and NSAID – had significantly higher cure rates in comparison to therapeutic trim only when the outcome assessed was a sound cow (56.1% versus 24.4%). Therefore, when treating early cases of lameness this is considered the best practice approach.

However, applying this protocol at farm level can be difficult. In many cases, it may not be the farmer treating these early cases of lameness, but an external foot trimmer instead. Therefore, it may not be apparent to the foot trimmer which cows are being presented for lameness and which are being presented for routine preventive trimming.

In this case, communication between the mobility score, vet, farmer and foot trimmer is important to ensure the necessary protocols are in place so NSAIDs are given to the cows that require them (Figure 5).

Improved communication between all of those involved in hoof health on the farm not only has benefits in terms of ensuring best practice, but can also be key in creating motivation and the drive for change. Implementing early detection and prompt effective treatment is a proven method of reducing lameness prevalence in a herd, and this provides a sound, evidence-based approach on which preventive strategies and long-term control can be built.

As the evidence base for treatment and prevention of lameness grows, it is important control plans are reviewed and edited accordingly to ensure herds continue to make progress in reducing lameness.

Latest news