31 Aug 2015

Anthelmintic resistance in sheep

The term anthelmintic resistance is not new to vets or most farmers and it poses an incredibly significant risk to the future health and profitability of the UK sheep flock; yet how many farm enterprises are actually trying to do something about it?

Anthelmintic resistance is the heritable ability of worms to survive a dose of anthelmintic that would normally be effective, and is present when 5% or more worms survive treatment. A telephone survey of 600 farmers (Morgan et al, 2012) revealed 19% of farms had carried out assessments on farm to know their own status, with 92% planning their own worm control strategies without the input of a vet or advisor.

My aim for sheep flocks is a two-part process – find out where they are in terms of anthelmintic resistance, and come up with a plan to ensure the wormers that are still effective continue to be so. So where do we start?

What is their status?

From my experience, this conversation usually starts when lambs have been wormed and yet still seem to be scouring/not gaining weight, or when samples taken post-treatment still show worm eggs are present.

The first thing to bear in mind is perceived treatment failure may not be due to resistance and there are a number of things to rule out first:

- Underdosing.

- Have sheep been weighed prior to treatment?

- Are they treating to the heaviest in the group?

- Have the guns been calibrated so the actual dose given is correct?

- Has the correct product been used?

- Has the treatment been administered correctly?

- If concerned about post-treatment FEC results, when were the animals treated in relation to the samples being taken? Too soon and it may not have had time to work, more than three weeks and it may be a new infection.

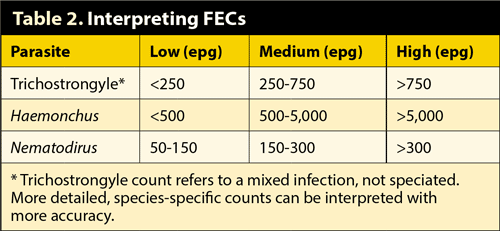

Once you have established the treatment given was appropriate, how do you diagnose resistance? There are two common ways to check treatment success – faecal egg count reduction tests (FECRT) and post-treatment faecal egg counts (FEC)/drench checks, but only one will help you to diagnose resistance and that is FECRT (Table 1).

A drench check is when, at a set time after treatment (seven days after levamisole, 10-14 after benzimidazoles and 14-16 days after macrocytic lactones), a FEC is taken to establish whether eggs are present.

A FECRT involves taking samples from the same group of sheep pre-treatment and post-treatment (same interval as drench checks) and calculating the decrease in the two counts to know whether there was a 95% or greater reduction, in which case you know resistance was not present.

The aim of FECRTs is to find out whether resistance is present and if it is, to what extent. For the full picture on farm this would need to be carried out for all five groups of anthelmintics, but at least benzimidazoles, levamisole and macrocytic lactones – all of which have been on the market for a number of years.

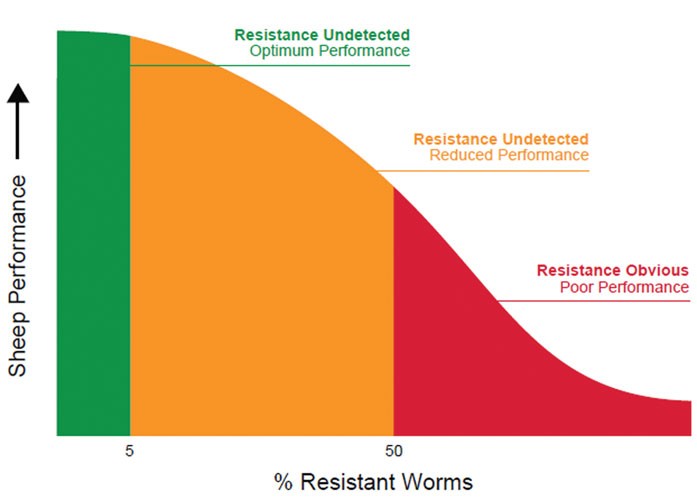

Figure 1 shows the scale of anthelmintic resistance on sheep performance. Green shows effective treatment where 95% or more are killed and performance remains unaffected. When in amber there will be an effect on performance, though it may go unnoticed, in contrast to the red zone at which point more than 50% of worms survive and treatment failure is obvious.

Knowing where each anthelmintic is on the scale for the farm can help you decide on treatment recommendations.

How to ensure anthelmintics stay effective

Even if farmers are not planning to find out their farms’ anthelmintic status, the following advice can still be applied to ensure any resistance is slowed down as much as possible and that worming groups remain as effective as possible for as long as possible.

Quarantine

Advising that all incoming animals are treated appropriately during quarantine will help prevent buying in problems.

All incoming animals should be yarded for 48 hours and be treated with either a group four (amino-acetonitrile derivatives; orange) or group five (spiroindole; purple) drench, as well as an injectable macrocytic lactone to prevent scab. After this period they should be turned out on to contaminated pasture.

Drench only when necessary

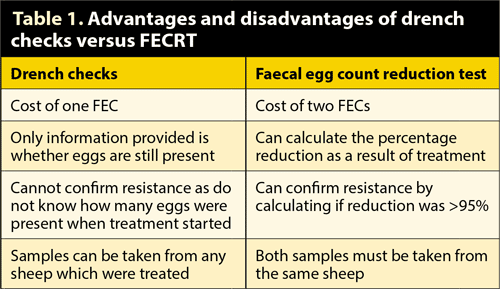

How do you know when to treat? The best way is by looking at a combination of factors – field history, animal history, time of year, age group, parasite forecast and FECs. FECs are very useful, but treatment cannot be decided on just that information; a conversation is needed to get the rest of the history before deciding on how to proceed.

It must also be remembered the correlation between FECs and number of worms present is poor in some species – for example, Nematodirus, the larvae of which cause significant damage, but until adults are present an FEC would remain low.

Adult ewes should not require regular worming unless Haemonchus is present on farm. Ewes should be wormed at lambing to help lower pasture contamination, but not pretupping unless in poor body condition.

Maintain a population of susceptible worms

Remember, when treatment is given it is only the proportion of the worm population inside the animals that is being exposed to the wormer. The proportion found on pasture depends highly on the pasture history – new leys, for example, will have a low proportion on pasture and are therefore safer grazing than recently grazed pasture that will be heavily contaminated.

In the case of “drench and move on to clean pasture” there is a low number of worms on the pasture to compete with any resistant worms inside the sheep and so this selects heavily for resistance and is no longer recommended.

By drenching and moving on to contaminated pasture for a few days after treatment, these resistant worms would be diluted, therefore slowing development of resistance.

This can also be achieved by leaving 10% to 20% of the group untreated, a strategy that should be adopted at lambing time when worming ewes.

Pasture management

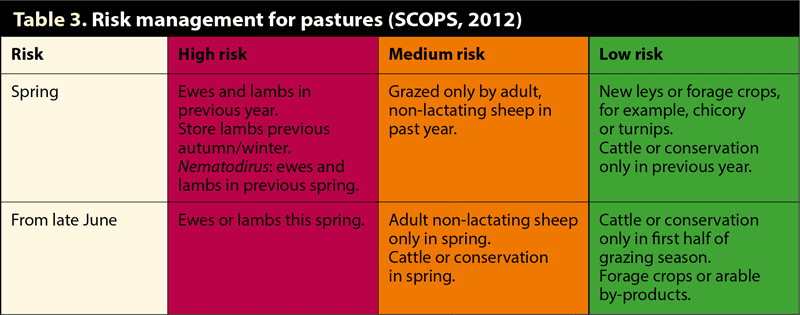

Knowing the history of the fields can help you determine whether it is low, medium or high risk (Table 3). For example, in spring, ground grazed by lambs the previous spring will pose a high Nematodirus risk compared to fields that were grazed by cattle the previous year.

Management decisions can also be made to try to lower the level of contamination on pasture by using certain groups of animals. For example, at weaning, move lambs on to low-risk pasture and leave the fit adult ewes on the current pasture to mop up as their own immunity will be higher than that of young lambs, therefore reducing the risk for the next time sheep graze on that pasture.

Conclusion

To summarise, knowing a farm’s resistance status is key to giving appropriate treatment advice to gain the most effective return on investment and to ensure resistant worms are not being given an advantage.

Farmers should be encouraged to gain knowledge of this and to implement best practice to slow resistance on their farms, to increase their profitability and sustainability in the future.